Sarajevo – Dreams

30 years ago, Serbia's brutal war of aggression against Bosnia and Herzegovina, supported by Bosnian Serb units, came to an end.

Sarajevo was besieged by the Serbian Army and Bosnian Serb troops for almost four years. Approximately 11,000 people were murdered by the besiegers, including 1,600 children. Approximately 56,000 people were wounded. There were few opportunities to leave the city.

I worked extensively in Bosnia and Herzegovina during and after the war, including in Sarajevo. The text and photos were created in 1997 for a book project on Bosnia and Herzegovina. Further texts will be on Tuzla, Zvornik, Banja Luka, Livno. The piece on Goražde has already been published.

Photographs: Astrid Bartl

Some terms are explained at the end of the text.

Sarajevo – Dreams

Edo

A blue fish swims in the window overlooking a square and an apartment block. The apartment block opposite bears no traces of shelling, no dark cracks or holes. This part was on the sunny side of the war. You can't see what it looks like on the other side, but it was exposed to shelling for years. The fish swims in front of the high-rise building, yet it does not move. It is stuck to the window on a piece of foil. No change.

At first, Edo was sceptical about whether he should talk to us for the book project. He has already done too many interviews and conversations and feels tired. He welcomed us into his studio, his retreat from external reality. In front of the fish at the window lies an unfinished painting on the floor. We sit at a battered coffee table and drink the obligatory coffee. An old radio tries to broadcast modern music.

"Our naivety was incredible. We didn't take the events seriously. We didn't want to believe that anyone would want to tear apart our Sarajevo, our lives. I remember Karadzic when he started out as a poet in 1972 or 1973. He was patriarchal, very rural. But we thought, okay, that's his way. We underestimated them because they were only a small circle in Sarajevo. But in the countryside they were strong, and we didn't feel their power. It was terrible to realise that someone wanted to destroy our centuries-old traditions."

People belong together, and the war was so brutal because what belonged together was torn apart by force. He still doesn't understand how it all happened. In Sarajevo, normality meant learning from others. The city's wealth was its diversity. ‘The best rock music, the best filmmakers and writers came from Sarajevo. This was the cultural centre.’ He does not mention the painters.

In the past, East and West met here. Different cultures lived together or side by side here. It was a heretical place in Europe that transcended traditional boundaries, creative and productive. It was a place of commonality and tolerance and solidarity in war. ‘Sarajevo was before the war what Europe may be in the future.’

Edo lived where he wanted to live. During the war, he travelled abroad for exhibitions, but always returned to Sarajevo. He did not want to flee; he wanted to experience what the war forced upon him, but also what it opened up for him. His perception changed. The small moments, the everyday, otherwise easily forgotten things gained significance. He had to get water and bread, find wood. Things you usually do without noticing. A smile, a small joy, the beauty of women in war became a great pleasure. Reflections on good and evil became uninteresting. Survival took up too much time. One day this war would be over, and the ethical position of belonging to the innocent, of having clean hands, of not having done anything to anyone, helped him to survive.

"I also wanted to test myself out of an aristocratic feeling, to see how I would behave in such a bad situation, what would happen to my illusions, my upbringing, my ideas about life. I told myself that I would be a loser if I stayed, but I wanted to see and experience it. Walter Benjamin said that if you are connected to death and destruction, then you understand. If not, then you don't even see."

Edo walked a lot through the city, witnessing another reality that hit him so hard that he became fascinated by it. ‘Death becomes close to you. Every time you went out, you didn't know if you would come back in the evening. That's a terrible thought. But this connection with death, the danger you are in, gives you a clearer view of people and things. You recognise and understand in a second.’

No place was safe; death could strike anywhere. The final frontier was always close to him. War as an experience becomes a privilege for the artist. But he has to protect himself from the depth of his feelings with irony and humour. The joke of the small installation in his studio is almost painful. It shows the everyday things of a life that would be played out in a ghetto under constant fire.

The tension of war, the energy and optimism have given way to fatigue and memories of the time before. He seems like a wise old man who has seen through life, but does not blame anyone for what has happened. When he laughs, his eyes look tired and sad or shine with mischievous joy. Art has become the meaning and essence of happiness. The outside world, which was so fascinating and dominant during the war, is once again assigned its subordinate place. Inner peace and harmony with oneself are more important than reality and truth. The propaganda and lies of recent years were too much. ‘Flaubert wrote in a letter: I have spent my whole life trying to find the truth. But the truth is stupid.’ All that counts is personal experience and the confirmation he finds in art and books. Cioran, Benn, Bernhard, Thomas Mann.

Reality was often too cruel to be completely trusted today; it only inspires creativity, the creation of something new, a nature of one's own, because there is much good hidden in it. Mysticism and irony help one to live in it.

Belief in the principle of community has been lost, individuality has gained in importance. ‘I am happy that I can look at life from a very private position as an artist. I have no obligations. I have my private, intimate experience and I insist on this experience because it allows me to see the good things in reality.’

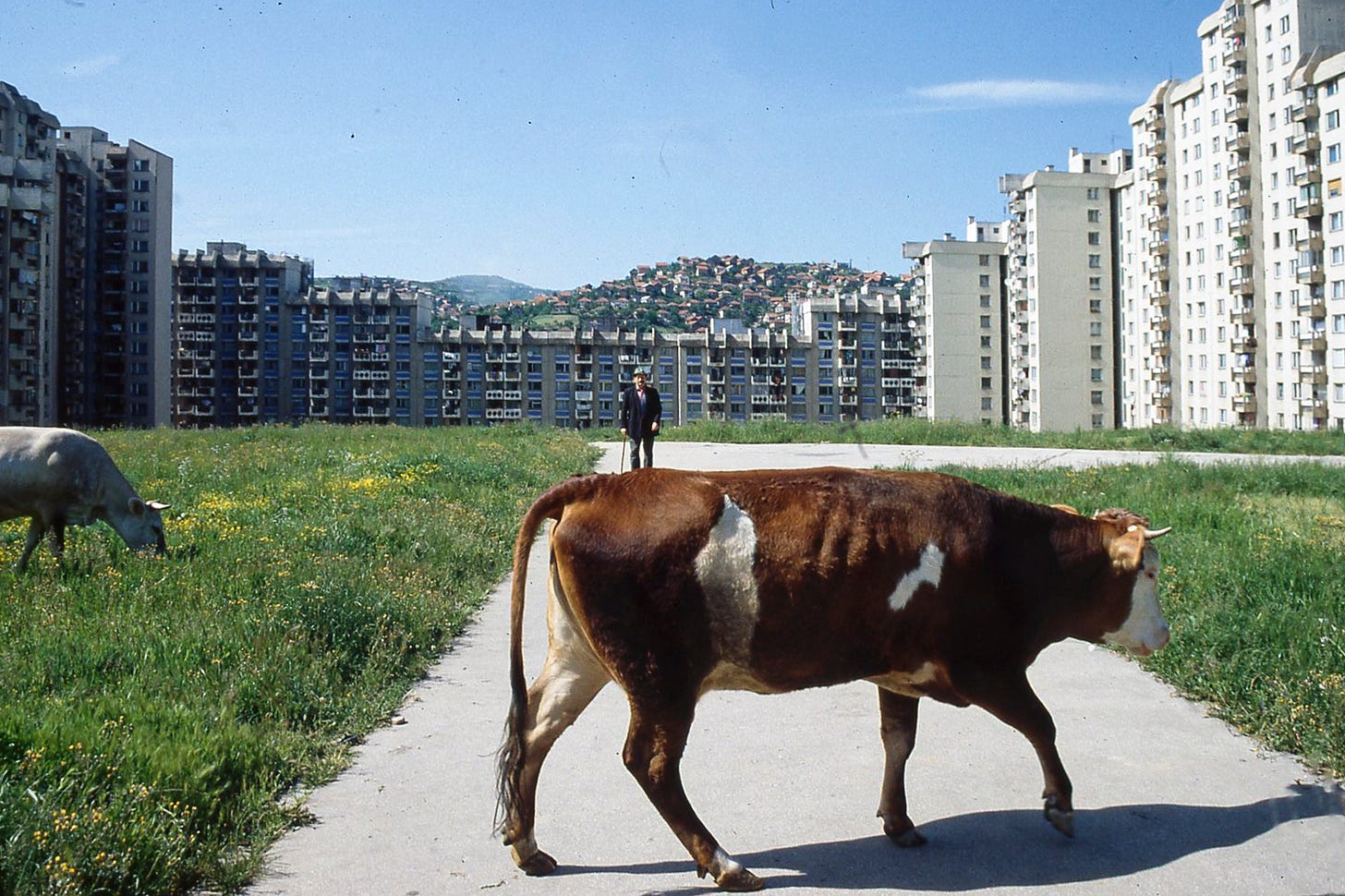

We leave his studio together and walk through the new development area. Flat, frayed craters from grenade impacts on the paths. In the city centre, many of these craters have been painted red. Here, dirt and dust collect in them. During the war, he walked to the city centre almost every day. In the evenings during the war, he often listened to the BBC. They broadcast news and played good music. ‘They had the best music to fall asleep to. The next morning, you woke up, went out onto the street and saw a dead child.’

*

Vera and Elfriede

"How can you divide Sarajevo? It's not Berlin. Sarajevo is such a small city. At first, it wasn't entirely clear what they really wanted. Then one day, Šešelj's people came to Grbavica from Serbia. We could see that they were all strangers. We know each other pretty well here in the neighbourhood. On 16 June 1992, I was no longer able to visit my children, who live on the other side of the Miljacka. We couldn't even talk on the phone anymore. That's when we knew things were getting serious. They divided the city. Our Serbian neighbours were also very affected."

Vera pauses briefly. Her friend Elfriede looks at her doubtfully and asks, ‘Don't you think they knew something?’

‘Come on. The people I knew in our neighbourhood didn't know anything.’

‘Yes, but in the countryside...’

‘Yes, in the countryside it was different. They were prepared.’

In Sarajevo, it was different, the two friends agree. Throughout the war, Vera and Elfriede were unable to see each other. Although both Vera and Elfriede live on the left bank of the Miljacka River, Vera lives in Grbavica, which was held by Bosnian Serbs during the war. Elfriede lives a few hundred metres upstream in a district held by the Bosnian government. And during the war, they were not allowed to visit each other.

Vera, whose father was Austrian and whose mother was Bosnian, is married to a Czech man who, because he is Catholic, is considered Croatian. That makes things easier. Vera's grandmother was Jewish. Her friend Elfriede is Austrian, who came to Sarajevo for love almost 30 years ago. They haven't seen each other for almost four years. When the children were younger, they celebrated Christmas together. Today, homemade cake, fruit from the garden, coffee and schnapps are on the table.

The new rulers made Vera feel that she was no longer welcome, even though she had lived in Grbavica for decades. But she also lived with the feeling of being on the wrong side, because her heart was on the other side, the one controlled by the government. Her usually calm, thoughtful voice becomes frantic when she talks about the shelling during the war. How Serbian units positioned artillery to fire at the other side. How the window panes shattered, how she was afraid, and then a Serbian soldier told her she didn't need to be afraid because they were firing from here to there.

"At some point, they also fired at us from over there. They were very small rockets. People were afraid at first, but the small rockets did hardly any damage. Much later, there were other, real rockets. But for us, how can I put it, we were happy because now they were shooting too. It was more joy than fear, and it was the same for our Serbs, who were with us."

It was a twisted world. A front line divided the city, families and friends. The people who didn't want to believe what was going to happen realised too late that their lives were in danger. It wasn't courage; Vera and her husband simply didn't think about leaving Grbavica. Although many did leave. But they were mostly young people. The old people stayed. ‘No, I wouldn't have wanted to leave. Everyone wanted to protect their home, their bed and their armchair.’ Shortly before the war began, her husband had to have a leg amputated. Vera had to do all the errands during the war. She went shopping when there were no soldiers on the streets. No one went shopping when there were soldiers on the streets. They were often drunk and no one controlled their arbitrary behaviour. But she was able to shop in the stores, unlike the Bosniaks. ‘They often asked for papers and then threw the Muslims out. I showed my Jewish ID and so I was pretty well off. But when you've seen everything that happened here. It was terrible. There was no such thing as a normal day here.’

Elfriede, in the other part of Sarajevo, was dependent on humanitarian aid. Every two weeks, there was oil, flour, sugar and some other food, but always too little. ‘Once we got an egg. But what do I do with one egg when there are five of us at home? I thought about it for a long time, then I had an idea. I made a soup with egg slices.’

Vera had other worries. Her life in the Serbian-occupied part of Sarajevo was different. She was afraid of the checkpoints, she was afraid that one day guerrilla fighters would also be standing in her apartment. Then anything could happen. It was the strangers from Serbia who brought the horror. Her old Serbian neighbours are defended and acquitted, because only very few of them participated. Fear was omnipresent in public. ‘On the street, my Serbian neighbours and I just nodded to each other. But in the houses and flats, it was different. Muslims, Serbs and Croats lived in every house. So you couldn't see where you were going. There were informers, but we knew who they were.’

In February 1996, Grbavica was reattached to Sarajevo. The city was no longer divided. Many Serbs fled Grbavica. Bosniak refugees moved into their apartments. Vera and her husband have become a minority again. The old trust between neighbours has been destroyed and now people don't know each other, they avoid each other. The distance between them and the refugees is great. Many of them want nothing to do with Serbs and Croats.

"I never thought about what nation I belonged to. Then, during the war, it became important. I had to hide my nationality, and I never thought that being Jewish like my grandmother would ever help me. I want to be Bosnian, but that nation doesn't exist. Or Chinese. Just not a Muslim, Serbian or Croatian."

Vera and Elfriede still don't understand why all this had to happen. Life was good for everyone before. But now it's destroyed. ‘Young people can change it again or make it even worse. But I hope it gets better. It's terrible, I'm going to die and I'll never know why all this happened.’

*

Faruk

We walk up the long ramp to the front door and open it. It is always open during the day, Faruk had told us. Faruk is not alone in his office. A colleague is sitting in front of a computer. Faruk turns away from his desk and greets us. He has a lot of work at the moment. New funds have to be applied for his organisation. Faruk was twenty years old when he was shot by a sniper in March 1995. A camera crew that happened to be there captured the seconds that changed his life on film. Today, these recordings are part of a computer video that he developed together with his colleague to draw attention to the situation of war wounded and people with disabilities in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

‘My dream is for Sarajevo to become the most accessible city for disabled people in the whole world, for it to be unique in its tolerance. Sarajevo should become an example for the whole world, an example of a good attitude towards people with disabilities. But that is the dream of my post-war personality.’

Faruk speaks slowly, pausing frequently. He seems to struggle to find the words. ‘The dream of my pre-war personality was for Sarajevo to be an international, vibrant city. Peaceful, with good concerts and beautiful girls. But now I want wheelchair users to be able to go wherever they want and need to go.’

During a hospital stay in New York, when he finally learned that he would be confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life, he decided to set up an organisation that would campaign for the rights of people with disabilities. ‘When they told me that there was no chance, that I had to prepare myself for a life in a wheelchair and that I had been treated incorrectly in Sarajevo, I lay in my room and looked out at Manhattan, I saw the lights after all those years of darkness in Sarajevo. I didn't know what to do.’

Now he runs an NGO with his colleague. Before the war, he was not interested in people with disabilities; he was as unaware of their situation as most people today are indifferent to the fate of the thousands of war-wounded and disabled. But that is exactly what he wants to change, and he wants to make Sarajevo a city where people with disabilities can move around normally.

‘We have such a great opportunity. In Sarajevo, as in other cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, so much has been destroyed. So much needs to be rebuilt. So we should take advantage of this opportunity and at least build all new buildings so that they are accessible to people with disabilities or flatten the pavements. We should be taken into account in every form of reconstruction.’

people with disabilities are not good for the reputation of a city that wants and needs to give the impression of regained normality, but which also dreams of the past. Sarajevo has created its own myth, which will live on because the war, the siege and the shelling created a different city. The war that wants to be forgotten, but is nevertheless omnipresent. On Ferhadija, the promenade in the city centre, young men in wheelchairs can be seen every day. They remind others of the war on a daily basis. They were all in the war together, some were wounded, others were not. And Faruk wants those who were unlucky not to be forgotten. He does not want pity, just the same rights and opportunities. But that is difficult in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

‘Before the war, people with disabilities were locked away in institutions. Now it's not like it was before the war, but there are still a lot of prejudices against us. Only now there are so many people with disabilities, most of whom were soldiers who defended the city, who fought for everyone else, that we can't be hidden away.’

Faruk enlisted in the army during the war. ‘I fought for my rights and defended Sarajevo, but it was also the excitement and danger that fascinated me. I was young at the time.’

But the absurdity of war soon caught up with him. During the war, he never thought he would be killed or seriously wounded. "I just imagined that I might get a bullet wound in my arm, a flesh wound, but nothing serious. I couldn't imagine having an arm or leg amputated or my spine injured. It was like people who don't want to believe that they will grow old one day. But time passes and suddenly they realise that they might need a ramp one day too.‘ Faruk interrupts himself with a laugh. ’Maybe I'm boring with my access options for people with disabilities. But that's a professional deformation. It's the most important thing for me."

He was hit by a sniper's bullet while walking as a civilian on the streets of Sarajevo. Faruk was seventeen when the war began. Twenty when he was wounded. Now he devotes himself to his task, his calling. It almost seems as if he wants to lose himself in his calling, as if the two have become one and the same. He speaks slowly, searching for words when he is not talking about his calling. When he does talk about it, the words flow out of him, not as if memorised, but as if coming from his innermost being. Sometimes there is an undertone of incomprehension as to why not everyone in the city sees it that way. It should be so easy, so obvious, in a city where so much has been destroyed by war, to think of all the people in the city when rebuilding. It has to be built anyway, so why not build it in such a way that disabled people also have access, so that they are not always dependent on the help of others when they want to go somewhere? But there is no hint of scepticism. He wants to achieve his goal.

‘When I go to an international organisation, the response is always that it's a great idea. How could we have forgotten that? We get the same reaction from our authorities. But when it comes to putting it into practice, it's a different story. I don't think they're unwilling to implement it, it's just laziness. They simply forget about it.’

So he and his colleagues continue to remind them. They have already achieved a great deal, but there is still much to be done. Life has become fast-paced since the war, which he thought would never end. ‘During the war, time stood still, or it ran backwards, or it ran forwards. It was confusing.’ Today, it seems to him as if the injury happened only yesterday. He feels no hatred, even though he cannot understand the people who bombed the city. Otherwise, his memories of the war are vague, because it was like a permanent repetition. Everything was the same, and now everything is different. ‘Of course, I have become a different person, but not just because I am in a wheelchair. There is something else that runs deeper.’

His relationship to the essential, to the spirit, the soul and the body has changed. Faruk searches for words to explain it. He turns to his colleague, who has been going about his work. They discuss it at length. Faruk nods in agreement again and again and then summarises what his friend said.

"He thinks that the mind is not important. The soul is our true self, even if it is often obscured by matter, by the mind. Most people present themselves differently than they really are because they are afraid. Although he is in a wheelchair, he is not afraid of himself. He has even discovered his true self. Since he has been in a wheelchair, he has realised that the material world does not matter, that physical appearance, which many people value so much, does not matter. People who can walk are no happier than I am."

For Faruk, his friend's words are the words he was looking for. The mind is there to satisfy our senses. Since he has been in a wheelchair, his mind has less to do and he can reflect more on himself. And both of them see people differently today than they did before.

"When I see a good-looking woman, my superficial reaction may be the same as it used to be. I see that she is attractive, just as I would have seen her before. But today I can also see what she is like inside."

*

Djordje

"If I hadn't gone through this war, I wouldn't know that everything is relative. The material world counts for nothing. What is important are feelings, dignity, love, honesty, being human. It was only during the war that I realised how dissatisfied and unhappy I was before the war because I was focused on the material world. People who have not experienced war cannot imagine how beautiful life can be. To experience a sunset and know that no one is going to shoot at you, to have enough water and food and no snipers trying to kill you."

Before the war, Djordje was an assistant at the university. He didn't want to believe in war and didn't take his friends who saw disaster coming seriously. During the war, he was an officer in the Bosnian government army and, as a doctor of philosophy, he was responsible for morale in his brigade for a while. The war had rendered the old standards obsolete. ‘Many had lost everything and felt they had to avenge their loss. In some situations, it was impossible to talk to them; they were wild and even threatened me.’ He was not always able to prevent soldiers from looting or committing acts of violence against prisoners.

His stern gaze suddenly softens. He smiles and tells a story about a quiet day at the front. They were lying in their position when suddenly they saw a little girl approaching them with a basket. It turned out that she was supposed to bring food to her father, who was stationed on the other side. They showed the girl the way and let her go, even though they had hardly eaten anything for days. The next day, the girl came back with a basket and brought them food and drink with a nice greeting from her father. ‘And there was no pork in it!’

Most people did not want the war, but it was difficult for many to free themselves from the web that had been woven by the nationalists. During the war, he had plenty of time to think about nationalism, observing and remembering his friends, and came to the conclusion that nationalism is a product of childhood and youth, when people grow up in a small, closed society where the only identity is the nation, where even children are told that their nation is better than others. ‘My parents were proud Serbs, my grandfather was an Orthodox priest. But I never heard anyone in our family say that Serbs were better than others. Only that all people are equal.’ The thinking in the countryside was different, and for Djordje, the war was a war of the village against the city.

Djordje remained in Sarajevo and never questioned whether he was on the wrong side. He had offers to switch sides and could have accepted a high-ranking position, but he wanted nothing to do with that kind of politics. During the war, some officers called him a traitor to the Serbian people and threatened to kill him. Today, he heads the office of an international organisation in Sarajevo and in this capacity has visited Republika Srpska, the Serb-controlled part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, several times. "Most people are happy to see me. I have never been rejected because I come from Sarajevo; they respect me. For most people, Sarajevo is an unfulfilled dream. I recently met an old colleague again in Banja Luka. For him, I was like a sign of civilisation."

He despises nationalists on all sides, in all countries. He considers them ridiculous figures, because being narrow-minded and nationalistic is not natural. It is natural to be open and tolerant. It is just as ridiculous when nationalists on one side call nationalists on the other side nationalists, which is part of everyday political life in Bosnia and Herzegovina. "I am Bosnian, not Serbian. But I am proud of my Serbian heritage. Why shouldn't I be? I am not responsible for what the nationalists have done. These mafiosi do not represent the Serbs."

Before the war, he felt like a citizen of the world who happened to be born in Yugoslavia, in Sarajevo. The war made him Bosnian because he was attacked as such. ‘I am not fanatical, I only become so when it comes to these nationalists. As long as they hold power, nothing will change.’

It will take a long time for life to return to normal, because everything has changed. Above all, people now have values that no longer point to the future, but are based on the past. He doesn't really fit into this new life in Sarajevo, but even now he has no intention of leaving. Instead, he confidently demonstrates that Sarajevo is still his city, despite everything.

‘I miss my friends and the climate of intellectual openness that prevailed in Sarajevo before the war. Now it is very reminiscent of a provincial town. It would be nice to live in a Sarajevo again where life is not dominated by ideologies, religion and nationalism, but by intellectual freedom and development. I hope I will live to see that before I die.’

*

Selma

‘During the war, there was a lot of solidarity. Now, after the war, that has diminished considerably. Perhaps people are afraid that it will happen again and are now keeping a lot to themselves, or perhaps we are starting to live like people in the West, thinking only about work and not caring about others.’

Selma would prefer to have the old Bosnian life back; she doesn't like the cold, Western lifestyle. However, it does have one big advantage, because those who only think about work forget more quickly and have little time for discussion. Then it becomes easier to live together again. Selma misses the others and is sure that others feel the same way. It's as if you were missing a hand. ‘I would never tell my child what happened, that the Serbs sat on the hills and killed us. I would never tell them that. But they'll probably learn it at school anyway.’

It would be best if everything could go back to the way it was before the war. A dream that can no longer become reality, because too much has changed. Before the war, things were better than during the war and after the war. The time before the war has been consigned to memory, while the time of the war has become experience. Experiences that returnees and foreigners do not have.

Before the war, Selma didn't care what religion her boyfriend was. Today, she could no longer be with a man who was not a Muslim. During the war, she witnessed couples breaking up because they were of different religions. ‘If a friend has a different religion, it doesn't matter. But with someone you want to spend your whole life with, it's different.’

The war has brought with it a desire for security that politics cannot give her. Selma has never been interested in politics; she only knows one thing, that with the current politicians it will be difficult for things to one day be as beautiful as they once were. Until recently, she was more optimistic. Then she translated for an international negotiator who was negotiating with Croatian, Serbian and Bosniak politicians. ‘First we spoke to a Croat in Mostar who hated Muslims. Then we spoke to our people here, who were also full of hatred. And then in Pale with the Serbian politicians, it was the same. I was so disappointed afterwards because I always thought that it would pass and we would live together again.’

During the war, Selma sometimes told herself that she hated the Serbs who sat on the hills because they had taken so much from her. But she doesn't feel that way; she sees this incredible hatred in others. She can understand it in people who have lost everything. She was lucky; her family survived. Their apartment was destroyed early in the war, but they soon found another one. The new flat had also been burned out, but one room, the kitchen and the bathroom were still intact. It was not much space for a family of four, which they also shared with a refugee couple. After the war, the owner of the flat, a Serbian woman who had fled, was supposed to come to visit. They held a family council to discuss how they should behave when the woman arrived. They agreed not to talk to her. The woman rang the doorbell, her father opened the door, said hello, nice to see you, and invited her into the flat. They then talked for hours.

The new flat was in a different neighbourhood, and Selma's contact with her few old friends who had stayed behind was interrupted. The journey was too long and too dangerous. "During the war, I was alone. I only had my family, and I didn't go out. It was only after the war that I read about the parties and bars that existed in Sarajevo during the war.‘ Dead bodies in the streets became commonplace. The first time she cried was when she took an old woman who was standing helplessly at an intersection by the hand and led her across the street. ’The old woman started crying and kept saying thank you, thank you, and God bless you."

Life after the war in Sarajevo irritates her. She feels that the last five years have set Sarajevo back 50 years. ‘It's unbelievable that there are now young people in Sarajevo who go to the mosque, that young women wear a headscarf, or that there are women who cover their entire faces.’ She is afraid that these people will gain even more influence, and she doesn't like the fact that children have to take exams in religion at school. But she feels the same way about religious people as she does about refugees. She has no direct contact with either group, except perhaps seeing them on the street. None of her acquaintances have been swept up in the new religiosity. In Sarajevo, they remain a small minority.

The war stole five years from Selma. Time that she is now chasing after, time that the present cannot give her back. "I have become stronger. I have seen a lot of blood, dead people on the streets. But I am happy because I survived and my family is alive. I am fine. I did not go mad like many others. I know what life means. Now I just don't want to miss anything, I want to have everything."

Explanatory notes

The text was written in 1997 for a book project on Bosnia and Herzegovina, which unfortunately was never realised. In addition to the texts, photographs of the city and portraits of the interviewees were planned. Further texts on Tuzla, Zvornik, Banja Luka, Livno and Goražde will be published.

When the interviewees referred to Bosniaks as ‘Muslims’ in the conversations, I left it that way in the text. The same applies when people spoke in general terms about “the Serbs”.

Bosnians – in the last census before the war in 1991, it was not possible to declare oneself as ‘Bosnian’, even if one wanted to. Those responsible insisted that one could only declare oneself as Serbian, Croatian, Muslim, Yugoslav or one of the other ethnic groups such as the Roma.

In larger cities such as Sarajevo, Banja Luka, Tuzla and Mostar, 10% or more identified as Yugoslav. It is estimated that over 25% of the inhabitants of Bosnia and Herzegovina either lived in or came from an ‘ethnically mixed’ family. During the war, however, people usually had to choose one of the three major ethnic groups.

Radovan Karadžić – Bosnian Serb politician and war criminal. He was arrested in 2008 and sentenced to life imprisonment in 2019.

Grbavica – district of Sarajevo

Miljacka – river flowing through Sarajevo

Šešelj people – Vojislav Šešelj is a politician, extremist and convicted war criminal from Serbia. During the wars in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the guerrilla fighters close to him, the ‘Bjeli Orlovi’ (‘White Eagles’) or Šešeljevci – Šešelj's people – committed the most serious war crimes.

The current President of Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić, was a close associate of Šešelj during those years.

Pale – 20 km from Sarajevo, it was the main town of the Bosnian Serbs during the war.

Mostar – a town in Herzegovina divided by the Nervetna River into a Croat-dominated and a Bosniak-dominated part. The most important Croat city in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Republika Srpska – entity controlled by Bosnian Serbs – part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The second entity is the Federation of Bosniaks and Croats. A third part is the Brčko District.

NGO – non-governmental organisation.